WAILUA — It is true that Robert M. Hamada is a master woodturner. But one look at his work and the term “woodturner” seems like an understatement.

Hamada is an artist in every sense of the word. Wood is both his passion and his canvas. And just talking about trees makes his face light up.

Hamada has been turning and working with wood since he was 12 years old. In June he will turn 92, but his work is as good as it has ever been.

In his case, with age came perfection.

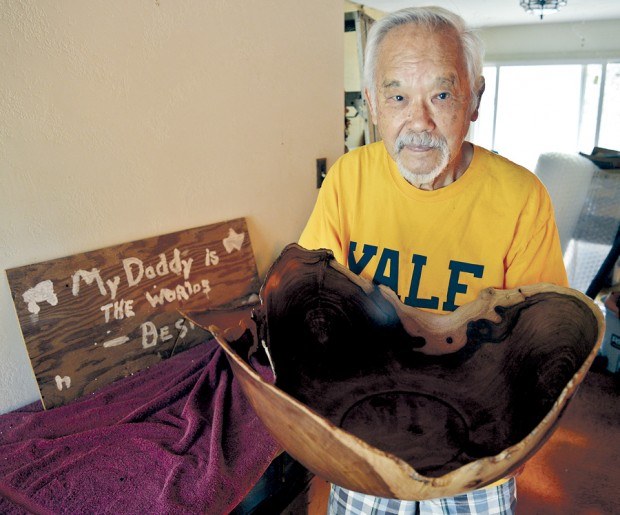

Over the years, Hamada has received many awards. And soon, one of his incredible wooden bowls — if you can even call them that — will be permanently displayed at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, one of the most-visited art museums in the world.

“It’s considered one of the top museums in the South,” Hamada said.

The bowl — which he considers one of his personal best — has already appeared in several art shows in Honolulu and here on Kaua‘i. It was cut and turned from a giant milo tree from the Kekaha area.

“You never cut down trees just to make a bowl,” Hamada writes in a book about his craft, put together by Pattie H. Miyashiro. “But if it needs to be cleared for some reason, I feel a sense of responsibility when a tree comes my way.”

When it comes to trees, Hamada says the milo is his favorite, although he also works with kou, kauila, kamani and hau.

“I use mostly woods of Hawai‘i … some are more beautiful than others,” he said. “The thing with the milo — (which) a lot of people don’t think applies to wood — to me it’s a very friendly wood. It does what I want the wood to do. Other wood will fight you from the start, give you a hard time.”

The milo, he said, is always his friend, turning out exactly the way he plans it to.

“That, in itself, is very unusual because you don’t even have that in human beings,” he said. “You may think you have a good friend and then the joker turns out to be a lemon. There are certain beauties in wood that’s not available in anything else.”

Each time he takes a new layer of shavings off of a chunk of wood, Hamada said he is discovering something totally new, something “no one else has ever seen in their life.”

It is from this that he draws his passion. But it is also the reason he tends to fight with himself during his work.

“Do I stop here and finish it up?” he often asks himself, unsure whether the piece of wood might reveal further beauty within. “It’s a fight, but it’s a pleasant fight. You enjoy that endeavor from the very start to the end. You start off expecting many different things and then it comes out better than what you even thought about.”

Hamada said very few people appreciate and attempt to acquire and bring out the beauty beneath a tree’s bark.

“In many cases it’s right below your nose. It’s almost like a woman. You may run into a girl that you see every day and all of a sudden, one day, you see the light. You see the beauty in her. There are other things that makes her beautiful, like her inner thoughts … the things you can’t see from the start.”

It is the same thing with a tree, said Hamada. The deeper you cut, the more you see and learn.

“No two trees are alike. It’s exactly like a woman, you know? It amazes me.”

One thing that sets Hamada’s work apart is his ability to appreciate and work with the wood’s scars and flaws.

“I’m not a chemist or a highly-educated person,” he said. “But I know near the decayed portion of the wood there are colors and textures that are found nowhere else.”

He uses those flaws to enhance the beauty and rarity of the piece, bringing out its natural character.

“There is something beautiful in age,” he says. “My policy has always been if you are not happy with that (flaw), go talk to God. He’s the one that put it there, not me.”

One thing is certain — Hamada puts his heart, soul and body into his work.

“Feel my hands,” he said. “I don’t have any fingerprints.”

Hamada’s art are of grand scale — always choosing the largest piece possible from the best part of the wood — thin as porcelain China and baby skin smooth, as stated in his book, “Robert M. Hamada: Master Woodturner.”

That smooth, shiny finished appearance is perhaps the biggest surprise of all. All of his pieces are unfinished. He uses no wax, lacquer, varnish or oil. Instead, he spends months hand-sanding each piece, giving it that finished appearance. Then he sands it again.

“Everything is done by hand,” he said.

Hamada was born and raised deep in the hills of Kapahi, Kaua‘i and now lives in a rural home in Wailua Houselots. He previously worked as an engineer at the Coco Palms Resort and Kaua‘i Surf. He is also a breeder of some of the finest big-game hunting dogs in Hawai‘i.

Over the years, Hamada has spoken in may classrooms about the importance of education and dreaming big.

“I never had the opportunity to go to college, so I made a promise to myself to send my children to the finest schools possible,” he writes in his book. “My son Ron went to Oakland College of Arts and Crafts and my son Don went to Duke. My daughter, Ann, went to Mount Holyoke College and Yale, and my granddaughter, Tiffany, is at Purdue (now at Yale working toward a masters degree). More than for the wood, I hope that I am remembered for encouraging young people to continue their education and for making them believe that they are capable of doing great things in life.”

• Chris D’Angelo, lifestyle writer, can be reached at 245-3681 (ext. 241) or lifestyle@thegardenisland.com.