Historic pieces of the once-dominant sugar industry on the island are coming down, one piece at a time. Some of them are visible to thousands of motorists a day, while others are tucked away behind high fences on side roads.

Historic pieces of the once-dominant sugar industry on the island are coming down, one piece at a time.

Some of them are visible to thousands of motorists a day, while others are tucked away behind high fences on side roads.

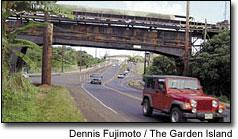

A portion of what is now the longest sugar flume in the state, where it spans Kaumuali’i Highway near the intersection of Rice Street, is to be torn down next month, said Allan Smith, senior vice president of Grove Farm Company and owner of the flume.

“For life-safety issues, that’s gotta come down,” said Smith, adding that small pieces of the rusting flume have already fallen onto the highway, though no injuries or property damage have been reported.

The flume still holds water, sort of, but leaks water onto the highway during rains, causing more potential roadway hazard, he added.

The flume used to carry tons of sugar from fields to the mill on a conveyor-belt system. It was built in 1954. Lihue Plantation Company leaders ceased sugar operations five years ago this month, so the flume and mill buildings serve no useful purpose now.

There were rumors that the flume would be coming down, rumors that started shortly after Lihue Plantation (LP) closed down, when plans were made to widen the highway to four lanes.

The reality is that the flume will be coming down before the end of the year, and possibly within the next two weeks, Smith said.

A contractor has been hired, and necessary permits (including a state Department of Transportation Highways Division traffic-control permit and some “ministerial” county permits) have been applied for, he added.

At the mill end of the flume, representatives of the new owners of the former LP and Kekaha Sugar Company mill areas, Pacific Funds, LLC, are selling the former LP mill power plant, said Lihu’e attorney Jonathan Chun, who represents owners of Pacific Funds on Kaua’i.

The sale of the power plant is in escrow, and the new owners intend to disassemble it, ship it to the Philippines, and reassemble it there, Chun said.

When the power plant was operating and LP workers were harvesting sugar, a byproduct of the sugar-production process, called bagasse, was burned in the power plant, and generated a substantial percentage of the island’s electricity.

At one point, a higher percentage of total electricity was generated on Kaua’i using renewable-energy sources (bagasse) than on any other island in Hawai’i.

Both the former Kekaha Sugar and LP mill sites will probably be designated U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Brownfield sites, meaning they contain lots of hazardous materials in the soil, Chun said.

That also means the owners will be eligible for federal grants and loans to help with the cleanup and redevelopment of the sites, he said.

The environmental-review process takes lots of time, and the cleanup itself could take one or two years, Chun explained.

Representatives of Pacific Funds have met with members of the Kekaha community to seek input on what kinds of projects they’d like to see on the former mill site, and community members said they’d like to see housing, commercial, industrial park, and recreational park uses there, Chun noted.

Back in Lihu’e, Chun said leaders of Pacific Funds are talking with officials with the County of Kaua’i about potential uses of the former LP mill area, but because environmental assessment will take quite a while, there are no firm plans for that parcel.