Learning from George Washington

By Cokie Roberts and Steven V. Roberts

On Christmas Eve 1783, private citizen George Washington finally went home to Mount Vernon. It was eight and a half years after he had assumed his post as commander of a Continental Army. It was more than two years after Gen. Cornwallis had surrendered at Yorktown. Keeping an army together those last two years was tough but necessary. Gen. Washington understood the value in staying the course.

Some members of the Bush administration have tried to draw parallels between what’s happening in Iraq today and what happened in America at the time of the Revolution. They’ve described the Baathist resisters as holdouts against a new regime, in the same way that Loyalists to the Crown in the American colonies resisted independence. It’s not an accurate analogy because most of the Loyalists, and all of the influential ones, left with the British. Early in the war, Loyalists decamped with the Redcoats from Boston; and at the end, the remaining holdouts against independence set sail with the British from New York.

But the lessons of tenacity and patience Washington taught 220 years ago are relevant in Iraq and Afghanistan today. During those eight long years between the first shots fired at Lexington and the completion of a peace treaty in Paris, victory at times seemed impossible. The American army was starving and freezing, unpaid and unprepared. Martha Washington and the other generals’ wives worked to soothe the soldiers’ spirits during the long winters at camp, while George lobbied the Continental Congress for more of everything — money, clothes, firepower.

The soldiers fought heroically, and occasionally the generals planned brilliantly. But what won the war was diplomacy. Had the French fleet not arrived off the coast of Virginia in October 1781, Cornwallis would not have been boxed in at Yorktown. And had the Spanish and Dutch not come through with loans, there would have been no money to support the long conflict. America probably wouldn’t have succeeded without George Washington at the helm, but Benjamin Franklin in Paris, John Jay in Madrid and John Adams at The Hague share a good deal of the credit.

After the military victory came the hard part. Without a definitive treaty, the British could not be trusted to simply pack up and leave; their forces occupied New York, Savannah, and the major Southern seaport, Charleston. So Washington had to keep his army together, on alert, for two years after Cornwallis’ surrender.

The head of the Southern command, Gen. Nathaniel Greene, negotiated British evacuation from Charleston at the end of 1782. When the American army entered the town, it was to the cheers of the citizens. Soon, however, the soldiers wore out their welcome. As the state was asked to finance the troops, South Carolina began to see Greene’s army as occupiers rather than liberators.

Rhode Island also balked at the cost of maintaining a militia to stay ever vigilant, guarding the coastline. And George Washington, with the help of Martha, kept increasingly restive soldiers in camp for two more long winters after they had achieved their great victory. Had the army disbanded, the negotiators in Paris would have been undermined dramatically in their ability to secure favorable treaty terms. America would have won the war but lost the peace.

That’s a lesson this country’s leaders understood at the end of World War II, when they invested troops and treasure in Europe and Japan. The United States has certainly shown staying power in those areas, with large, sometimes unpopular U.S. military contingents in both places almost 60 years after the war’s end.

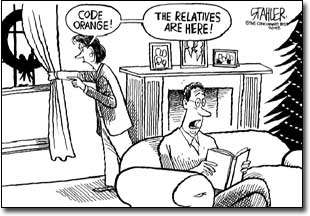

The capture of Saddam Hussein has temporarily stopped the erosion of support for the war in Iraq in recent public opinion surveys. But the violence in the post-invasion period still has some politicians calling for a speedy withdrawal of American forces. That would be a mistake. It would also be a mistake to ignore diplomacy. The chances of “winning the peace” are much greater with the international community behind an American military presence.

George Washington understood the importance of diplomacy as he bided his time at winter camp. The negotiators in Paris, backed by a military ready to take action if necessary, were able to craft an agreement highly favorable to the new nation. And General Washington could finally resign his commission and go home for Christmas.

Copyright 2003, United Feature Syndicate, Inc.